Friday, September 30, 2005

Hillel and Ezra - Shabbos 153b

Thursday, September 29, 2005

The Wheel of Poverty - Shabbos 151b

בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵל לִפְקֻֽדֵיהֶם וְנָתְנוּ אִישׁ כֹּפֶר נַפְשׁוֹ לַֽיהוָֹה בִּפְקֹד אֹתָם — If you uplift the heads of the Jews according to their count, and they shall give, each person, the redemption of his soul to Hashem when they are counted. The trop is a kadma v’azla.

Wednesday, September 28, 2005

Thinking About Weekday Matters on Shabbos -

Tuesday, September 27, 2005

Turning to False Gods - Shabbos 149a

Sunday, September 25, 2005

Terms of Borrowing Objects and Terms of Borrowing Money - Shabbos 148a

The Definition of the Prohibition of Cleaning on Shabbos - Shabbos 147a

Destructive Activities for the Purpose of Shabbos - Shabbos 146a

Thursday, September 22, 2005

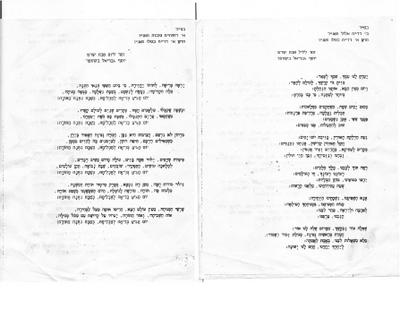

Zemiros Translation

A talmid of Ohr Somayach who is B"H getting married soon asked me to tranlate my zemiros so he can include them and their translations in his chausnah bentcher. So here are the translations to the texts:

A talmid of Ohr Somayach who is B"H getting married soon asked me to tranlate my zemiros so he can include them and their translations in his chausnah bentcher. So here are the translations to the texts:

The Night Zemer:

You destined us, Your nation, Your name to glorify,

You commanded your holy people, the world to illuminate,

And a day akin to [the World] to Come, You granted to us,

A special gift, because You chose us.

The sum of six days, we are mired in toils,

The [ultimate] purpose is concealed, by pursuits of livelihood,

When, however, the footfalls of Friday are overheard,

Again to be uplifted, we yearn.

[Then] comes the lighting of candles, leaving day-to-day,

We enter the "field of sacred apples,"

In the mornings, to "the ancient," in the afternoons to "the miniature countenance,"

Remember us and we will recall You, purify mundane life.

See into our hearts, King of Kings,

Our will [is to do] Your will, Sustainer of the worlds,

Our yearnings should be accepted, One who discerns the inner [workings],

Hear our requests, fill us with holiness.

Please cause to flow down to us, our additional souls,

[Our] portions grant us to taste, in Your supernal rest,

To love and to hold in awe, purify our hearts,

Educate us, refine us.

One more request we shall ask of You, From on High send us Light,

The precious [light], from Genesis hidden, the quality of "Remember" and Keep,"

Fulfill the requests of our hearts, in absolute truth,

The Day Zemer:

Note: Much of this Zemer consists of allusions to the Aggadata concerning the Giving of the Torah in Perek Amar R' Akiva in Meseches Shabbos.

Creation was afraid, that He would return it to desolation, for on the sixth day He set a condition,

The Bride preceded "We shall do" to "We shall hear," on Shabbos it [Creation] was perfected, found rest.

The day that Creation attained its purpose, on Shabbos the Torah was given!

And at the moment they accepted [the Torah], angels hastened, and tied two crowns on everyone,

When they sinned, they relinquished their decorations, [but] on Shabbos Moshe adorns us with them.

The day that Creation attained its purpose, on Shabbos the Torah was given!

"Stink" was not written, [as a sign of] endearment to us, the [previously] hidden treasure he left in out hands,

Those whose path is to the left, their spirit shall expire, [but] for those who turn to the right it is an elixir of life.

The day that Creation attained its purpose, on Shabbos the Torah was given!

The mouths of the seraphim, denigrated [Moshe] born of woman, he who ascended on High [Moshe] responded with words:

To those who perform crafts, is the task [of] Resting [on Shabbos], [with] Shabbos we shall come and rectify the world.

The day that Creation attained its purpose, on Shabbos the Torah was given!

The revelation of the secrets of the canopy, the giving of the law, is found in the chapter of the broker of Torah [R' Akiva],

The kingship of Torah, a heritage to [any] one who takes it, today shall delight us in its abundance of light.

The day that Creation attained its purpose, on Shabbos the Torah was given!

The roots of the Rest, likened to the World to the Come, uplifted a nation above free will,

The sign of the Rest, and the light of the Torah, will testify to the sanctity of the cherished nation.

The day that Creation attained its purpose, on Shabbos the Torah was given!

Tuesday, September 20, 2005

Fascinating Thunderstorm Minhag!

ודע בני כי היראה מן הברק ורעם טובה לאדם ורפואת הנפש כי יראת אלהים תוסיף ימים והאלהים עשה שייראו מלפניו. יש נוהגים לפתוח חומש פרשת עשרת הדברות בסדר יתרו בעת הברק והרעם ואין לשחוק עליהם במנהג זה, כי הטעם הוא בעבור כי שם נאמר ויהי קולות וברקים (שמות י"ט) כלומר זכות אותן הקולות והברקים של מתן תורה אשר קבלנו מגין עלינו מן הקולות והברקים האלה המסוכנים, ושם נאמר גם כן אל תיראו כי לבעבור נסות אתכם בא האלהים, ובעבור תהיה יראתו על פניכם לבלתי תחטאו:

Moving Bones on Shabbos - Shabbos 143a

Adam Chashuv - Shabbos 142b

Tuesday, September 06, 2005

Treatment of the Dying - Shabbos 151b

Monday, September 05, 2005

Typo in Meshech Chochmo

I think there's a typo in the last line.

נ"ל שיש טעה"ד בשורה האחרונה.

וצ"ל: ודאי כל זמן שלא הי' כבוש וחלוק בארץ [לא] היו מקיימים בזה ישיבת א"י